The following is my prepared transcript for a talk given for StoiconX-Alberta.

I appreciate the opportunity to speak to you all today. In my talk here Coherence, the Difference Between Truth and Opinion, I want to put forward and explain key ideas on knowledge that have really helped me understand and apply Stoicism in my day-to-day life. The philosophy dealing with knowledge and how we know things is called epistemology, and the Stoics have their own epistemology, based on our experiences or engagement with the world. For me grasping this theory of knowledge was a major turning point in my understanding and application of Stoicism. Virtue after all is a specific type of knowledge, practical knowledge of how to live well, so how we go about acquiring that knowledge is important. It is also key to understanding the Stoic theory of emotion, our emotions for the Stoics are cognitive and are based on our knowledge and how we judge events and how we engage with the world.

So, what is Stoic epistemology? Well, it is based on what is called adequate impression (phantasia kataleptike in Greek), this is the Criterion of Truth for the Stoics. Impressions are in a sense how we interact with the world, impressions include our 5 basic senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell, but also our own thoughts. In short, Impressions are how we perceive the world. Not all impressions, however, are adequate impressions. In order to be an adequate impression, the impression needs to first of all come from a real object, according to a real object, and in such a way that it could not come from anything other than a real object. They need to be clear and distinct. Epictetus gives an easy example of an adequate impression, the impression that it is day, if we are outside midafternoon and have the sun beating down on us it would be impossible to form an impression of it being nighttime.

That is not always going to be the case, our impressions are not always clear and distinct. Our senses may be limited or blocked. Perhaps it is too dark to see well enough, or the object is too far away; a cow in a field from a distance might look like a bush, or a bush like a cow. We are getting an impression through our vision, but because it isn’t clear and distinct, we cannot adequately discern what it is we are seeing.

One more thing with impressions, they are not just the sense data that we perceive. They also contain automatic value judgments, essentially whether something is good or bad. This value judgment also creates an impulse or motivation, we are naturally inclined to move towards what we think is good, and away from what we think is bad. The trouble is we want to make sure we are moving towards what is truly good, not just our opinion of what is good.

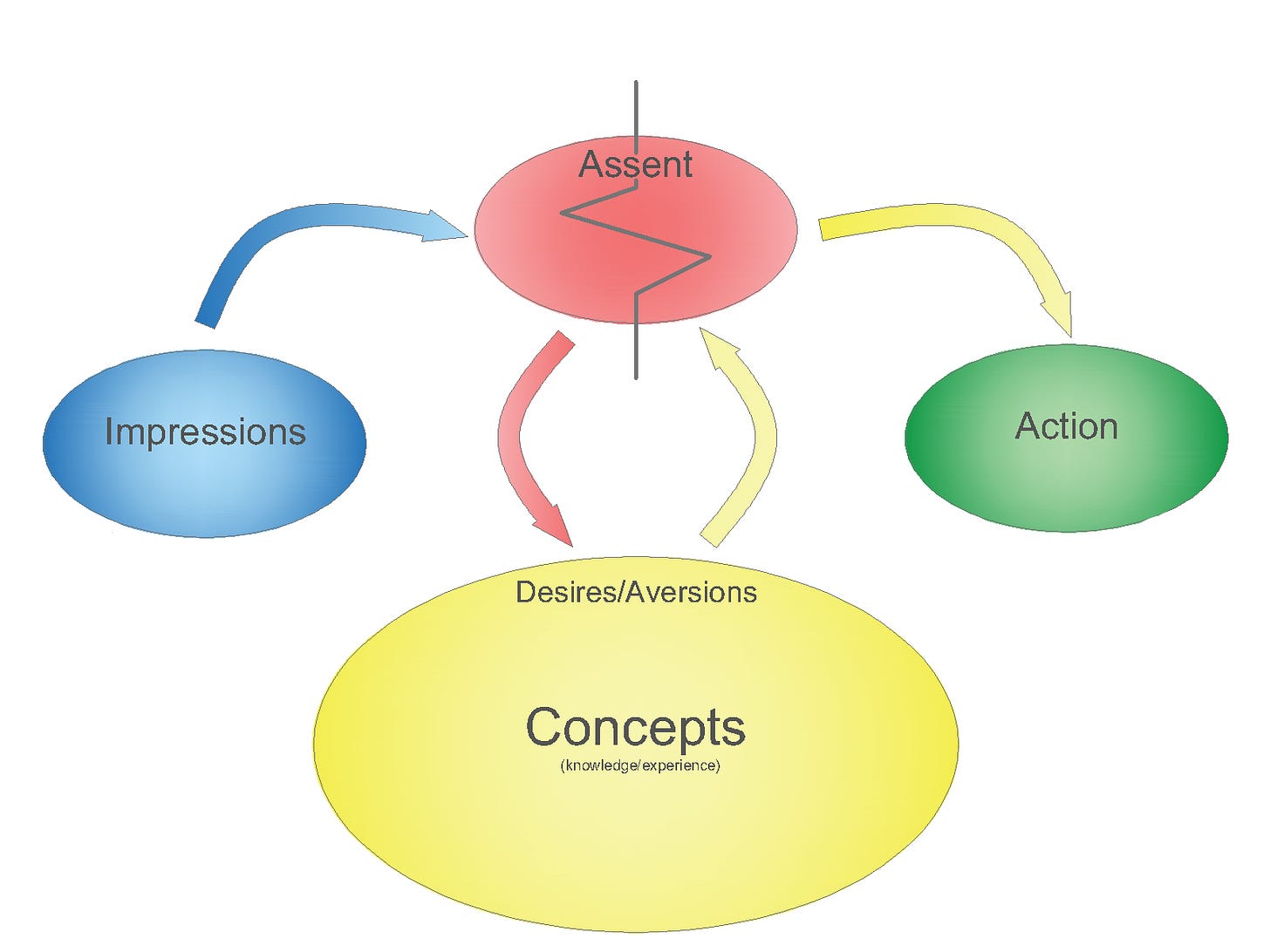

After receiving impressions, the next steps in the process are assent, and then action. Assent means agreement, so when we assent to the impression, we have received we are agreeing with it. We also have the options to reject it, or to withhold assent of the impression. We don’t want to assent to every impression that is presented to us, because the value judgments that came as part of the impression could be wrong, and mistaken judgements lead to mental disturbances. In order to judge the impression, we need to compare it to the concepts we have previously learned through our experience, or through learning Stoic theory. Epictetus refers to these as preconceptions, and it is with these preconceptions that we want to test and judge our impressions to ensure we do not assent to impressions with false value judgments.

Additionally, we want to test our impressions against our preconceptions of Nature, to ensure that we are judging them based on how things truly are, rather than our flawed opinions. Aligning our impressions with nature helps us make them coherent, free of contradiction. That is really the whole point of learning Stoic theory, to alter our view of the world to enable us to judge events correctly and live well and free of disturbing emotions. Our preconceptions when properly applied can help rid us of contradiction and help keep our desires and aversions coherent. And preconceptions are something we all have, as Epictetus notes in Discourses 1.22.

Preconceptions are common to all people, and one preconception doesn’t contradict another. For who among us doesn’t assume that the good is beneficial and desirable, and that we should seek to pursue it in every circumstance?

-Discourses 1.22.1

Our errors arise when we apply preconceptions within particular circumstances, people apply them to their opinions, or their wrong ideas. Whereas what we should do is apply them in accordance with nature. Or as stated by Chrysippus “living according to one’s experience of those things which happen by nature … [f]or our individual natures are parts of universal nature”. (DL 7.87)

Epictetus provides several different preconceptions throughout the Discourses. In Discourse 1.11 On Family Affection, a man comes to Epictetus, miserable because of the distress his children cause him. His daughter was recently sick, and it troubled him so much he couldn’t bear to be around her and stayed away until she was feeling better, saying that it is only natural to behave in such a way. Essentially the man’s impression is that his daughter's illness is a bad thing, and when we judge things to be bad, we will be inclined to avoid them.

Epictetus isn’t buying that and picks out two preconceptions to apply to the situation to convince the man he was wrong. First, loving one's family is natural and good. And second, that what is reasonable is good. If two things are good, then there can be no conflict between them. Epictetus aims to point out that abandoning those you love is not a reasonable thing to do, and therefore not good, and not done because of love, and Epictetus does this with some Socratic questioning.

Since you had such affection for your child, then, was it right for you to rush off and leave it? And its mother, has she no affection for the child?

‘Of course she does.’

Should its mother too have abandoned it, or not?

‘She shouldn’t have’

And its nurse, does she love it?

‘She does,’ he said.

Should she too have abandoned it?

‘In no way.’

And its attendant, does he love it?

‘He does.’

Should he too have abandoned it, then, and gone off, so that the child would have been left on its own without help as a result of the great affection in which it was held by you, its parents, and all who had charge of it, and would quite possibly have died in the hands of people who had no love or care for it?

‘Heaven forbid!’

-Discourses 1.11.21-23

In doing this Epictetus shows the man that his actions were not reasonable and therefore not good. And since they are not good, they also could not be the result of loving one’s child, but instead from a mistaken judgement left unexamined, really the man was judging his child’s sickness from his own perspective, and not in accordance with nature, or even from his daughter’s. Looking at it from his wife's perspective, the nurse and attendant helped move him to a judgement that is in accordance with nature.

What we are aiming for is to have our preconceptions applied correctly in accordance with nature. When we do this, we act appropriately, in a manner where we are free from disturbance and can experience a serenity. These resulting actions which would be from adequate impressions, tested against preconceptions, and viewed as in accordance with nature, also go on to build our concepts or knowledge that will help us deal with the impressions in the future.

If we return to the impressions we started with, remember they come with value judgments. Some of those value judgements come from the way that we have habitually judged things in the past. The man from Discourse 1.11 who was distraught at his child being ill, may still be distressed and want to leave when his next child falls ill. Though with the help of Epictetus he would hopefully be able to judge that impression correctly, stay with his child as would be appropriate. If he does this a few times he may come to see that his child being ill is not in fact bad, and what is truly good is him staying there loving and supporting his child. With enough work and positive habits when his children fall ill, he will no longer have the value judgement that their sickness is bad, and will no longer have the motive or impulse to flee. So our correct judgments can actually modify the way we perceive impressions in the future, by modifying, or removing that initial value judgement to be more in line with Nature.

A personal, and kind of silly, example for me. One of my sons is quite independent, he likes doing things for himself. Sometimes though this resulted in him making a mess. I used to get quite angry when he would make a mess pouring himself a glass of milk for example. If the jug was half or so full, he could do it on his own no problem. But any fuller would be a challenge, sometimes resulting in him dropping the entire jug and making a huge mess. And this would make me quite upset, why couldn’t he just ask for help? Why didn’t he know that when the milk was too full?

Eventually I realized, as anyone looking at the situation from outside would realize that my anger and frustration wasn’t a rational response. Instead, it was being created from my mistaken judgement that spilt milk was something bad, and perhaps further mistaken judgments that my son was intentionally being inconsiderate. So, I took some time and reflected and thought about that. Another preconception from Epictetus, nothing outside our own sphere of choice can be bad. Spilt milk is outside my sphere of choice so it really can’t be bad. Also, as children grow, they become more and more independent, which means they will be making mistakes, that is natural and good. So spilt milk isn’t bad, and kids learning and making mistakes is natural and good. Problem solved right? I never got mad or upset when my son made a mess again.

Well no. I had long been in the habit of getting angry, and not been in the habit of carefully examining impressions. So, I still got mad, the impression still carried the value judgement of the event being bad, and I was not disciplined enough to stop that impression and judge it properly before assenting to it. But I realized and knew that I shouldn’t be getting mad, that is an error on my part, and as soon as I realized that I stopped, calmed down, apologized to my son, and then helped clean up the mess. After a few times of this I was no longer having outbursts of anger, though I still was frustrated and upset internally. This made dealing with the situation much easier, I am not getting upset, my son isn’t getting upset in response to my getting upset. Clean things up and move on. A little while after that I noticed that I wasn’t getting upset at all, the impression had no value judgement of the mess being something bad. Just the impression of the mess that I could judge as it was, and then deal with appropriately. This also created a very nice and hard to describe feeling, kind of blissful, I am assuming this is what is meant by tranquility. And it was a major turning point in my understanding, and actually choosing to stick with Stoic philosophy.

Examples like these are relatively simple and straightforward. The full task takes much more effort and dedication, what we need is a complete and interconnected system of preconceptions in order to apply them correctly in every situation, and we need to take the time to examine them properly.

But it is impossible for us to adapt these preconceptions to the corresponding realities unless we have subjected them to systematic examination, to determine which reality should be ranged under which preconception.

-Discourses 2.17.7

Who among us doesn’t talk about ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and about what is ‘advantageous’ or ‘disadvantageous’? For who among us doesn’t have a preconception of each of these things? Is it properly understood, however, and complete?

-Discourses 2.17.10

Elsewhere, in Discourses 2.11 Epictetus speaks of systematically examined preconceptions. Systematic in that they all need to fit and be coherent with each other, free of conflict because there will be no conflict between what is good. And a passage from Marcus highlighting the importance of judging things correctly and in accordance with nature.

Venerate your faculty of judgement. For it depends entirely on this that there should never arise in your ruling centre any judgement that fails to accord with nature or with the constitution of a rational being; and it is this that guarantees freedom from hasty judgement, and fellowship with humankind, and obedience to the gods.

-Meditations 3.9

In this talk I have tried to share my experience with the importance of some aspects of Stoic epistemology. First of all we need to put the effort in and examine our impressions correctly and according to nature, the importance of having our preconceptions and building an interconnected system through close examination and proper application. I hope you can take something from this to improve your understanding and application of Stoicism. Thank you for your time and attention.